Abstract

Background:

Post-molar pregnancy gestational trophoblastic tumours (GTT) have been curable with chemotherapy treatment for over 50 years. Because of the rarity of the diagnosis, detailed structured information on prognosis, treatment escalations and outcome is limited.

Methods:

We have reviewed the demographics, prognostic variables, treatment course and clinical outcomes for the post-mole GTT patients treated at Charing Cross Hospital between 2000 and 2009.

Results:

Of the 618 women studied, 547 had a diagnosis of complete mole, 13 complete mole with a twin conception and 58 partial moles. At the commencement of treatment, 94% of patients were in the FIGO low-risk group (score 0–6). For patients treated with single-agent methotrexate, the primary cure rate ranged from 75% for a FIGO score of 0–1 through to 31% for those with a FIGO score of 6.

Conclusion:

In the setting of a formal follow-up programme, the expected cure rate for GTT after a molar pregnancy should be 100%. Prompt treatment and diagnosis should limit the exposure of most patients to combination chemotherapy. Because of the post-treatment relapse rate of 3% post-chemotherapy, hCG monitoring should be performed routinely.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Gestational trophoblastic tumours (GTT) form a family of rare diagnoses, including molar pregnancies, invasive mole, choriocarcinoma and placental site tumours. These are each characterised as arising from the cells of conception producing hCG and having extremely high sensitivity to chemotherapy (Seckl et al, 2010). Although these tumours are rare, they have been routinely curable with treatment for over 50 years (Hertz et al, 1956). One of the main considerations of current treatments is to maintain cure rates, while minimising exposure to excess chemotherapy, in view of the potential negative effects on fertility and future second tumour risks (Rustin et al, 1996; Bower et al, 1998).

In the United Kingdom, all patients diagnosed with a molar pregnancy are registered centrally for hCG monitoring and followed up, with the patients requiring treatment receiving care in the two units at Charing Cross Hospital in London and Weston Park Hospital in Sheffield. This centralised approach to care has allowed the development of considerable clinical experience and the collection of accurate data on outcomes from large numbers of patients (Bower et al, 1997; McNeish et al, 2002; El-Helw et al, 2009).

Despite the overall high cure rates in GTT, there remain some areas of ongoing clinical debate. These include the optimum schedule of methotrexate (MTX) administration, the comparative benefits of single-agent therapy with MTX or dactinomycin for low-risk patients and the appropriate point to locate the cut-off values between low- and high (or intermediate)-risk patients, and hence their initial treatments. However, the development of routinely curative chemotherapy for GTT predates the introduction of randomised clinical trials in cancer treatment by a number of decades, and as these rare illnesses have extremely high cure rates with their established therapies, developing prospective trials remains challenging (Alazzam et al, 2009; Lertkhachonsuk et al, 2009).

In this paper we present the demographics, disease stage, prognostic scores and treatment outcomes for 618 women treated for post-molar pregnancy GTT at Charing Cross Hospital in the decade 2000–2009. The data in this series may be of value in designing clinical trials, discussing individual risks and treatment options with patients, and supporting the development of centralised services in other countries.

Patients and methods

Patient database and selection

The electronic database of the Trophoblastic Disease Centre at Charing Cross Hospital in London was reviewed for all cases of GTT following molar pregnancies treated between 2000 and 2009. The patients included in this series all had a prior uterine evacuation, confirmed molar histology, met the Charing Cross Hospital guidelines for treatment and had a follow-up of at least 1 year after the completion of therapy.

The guideline indications for treatment after a molar pregnancy include the following components: heavy PV bleeding, rising hCG levels over a 2- to 4-week period, an hCG plateau of 4 weeks or longer, or a serum hCG level >20 000 IU l−1 more than 4 weeks after evacuation (Savage et al, 2008). Patients meeting these criteria were then assessed according to the FIGO scoring system as shown in Table 1, and grouped as either low risk (0 to 6) or high risk (>6; Ngan et al, 2003).

Pre-treatment assessment

All patients were assessed clinically with a Doppler ultrasound scan of the pelvis, a chest X-ray (CXR) and an updated serum hCG level. On the basis of this assessment, patients were given a prognostic score according to the FIGO scoring system.

All patients with pulmonary metastases visible on the CXR went on to have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and a brain MRI scan.

Treatment protocols

The standard first-line therapy for patients with a FIGO score of 6 or lower was the Charing Cross Hospital MTX and folinic acid (FA) regimen. A small number of patients with adverse characteristics, such as heavy bleeding, hCG levels over 250 000 IU l−1 or a contraindication to intramuscular administration were commenced on first-line treatment with either D1-5 dactinomycin or the EMA–CO combination regimen.

Patients with CXR-detected pulmonary metastases received CNS prophylaxis with intrathecal MTX (12.5 mg) every 2 weeks for three doses, with treatment timed to coincide shortly after one of the i.m. doses of MTX.

During treatment, patients had their serum hCG levels measured twice weekly, and three static or two rising hCG values were defined as drug-resistant disease and the patient was changed to a more intensive therapy.

The next treatment regimen was determined by their current hCG levels, with those with hCG levels <300 IU l−1 receiving single-agent dactinomycin and those with hCG levels of>300 IU l−1 commencing on EMA–CO. Patients developing second-line resistance to dactinomycin were changed on EMA–CO chemotherapy.

For the small number of post-molar pregnancy patients scoring in the high-risk category (WHO score >6), the first-line treatment was the EMA–CO regimen. Any of these high-risk patients who developed resistance or excessive toxicity were changed to the taxol–etoposide/taxol–cisplatin (TE/TP) doublet regimen (Wang et al, 2008).

In all cases, chemotherapy treatment was continued until normalisation of serum hCG level (<5 IU l−1) and then for an additional 6 weeks of consolidation therapy.

For a small number of patients with drug-resistant disease or relapse localised to the uterus, a hysterectomy was performed.

After completing chemotherapy, lifelong hCG follow-up was commenced and patients were defined as having had a relapse if, in the absence of a new pregnancy, hCG levels start to rise after the hCG level has been in the normal range for 6 weeks.

Treatment regimens

Methotrexate/folinic acid

MTX 50 mg i.m. days 1, 3, 5 and 7, and FA tablet 15 mg days 2, 4, 6 and 8, repeated every 14 days.

Dactinomycin

Dactinomycin 0.5 mg i.v. days 1–5, repeated every 14 days.

EMA–CO

D1: etoposide 100 mg m−2, dactinomycin 0.5 mg, MTX 300 mg m−2. D2: etoposide 100 mg m−2, dactinomycin 0.5 mg. D8: cyclophosphamide 600 mg m−2, vincristine 0.8 mg m−2, repeated every 14 days.

Results

Patients treated and FIGO scores

Between 2000 and 2009, 9010 women with molar pregnancies were registered for screening at the Charing Cross Hospital. During this 10-year-period, a total of 746 patients were treated at the Charing Cross Hospital for GTT, following a molar pregnancy; and of these, 128 have been excluded from this study primarily because of overseas residence, unverified histology or incomplete follow-up.

Of the remaining 618 post-mole GTT patients, 91% had a diagnosis of a prior complete molar pregnancy and 9% developed GTT following a partial molar pregnancy. The median age at the start of treatment was 32 years, with an overall age range between 15 and 56 years. The results of the FIGO prognostic scoring are shown in Table 2, with 579 (94%) of the 618 patients falling into the low-risk (0–6 FIGO score) category and only 39 (6%) patients of the study population falling into the high-risk group.

Treatment outcomes

Low-risk group

The overall results of the low-risk treatment group of patients are shown in Table 3. For the 579 FIGO low-risk score patients, 554 patients received first-line treatment with MTX/FA, with 316 patients successfully completing their therapy using this regimen alone, producing an overall successful treatment rate of 57%. For the 238 patients who started MTX/FA but required more intensive treatment, the choice of second-line treatment was dependent on the hCG level at the time of the introduction of the second-line treatment. For patients with an hCG level under 300 IU l−1 single-agent dactinomycin was the standard treatment, whereas for women with an hCG level in excess of 300 IU l−1 at the time of treatment escalation EMA–CO was the treatment choice. Of the 96 patients treated with the second-line dactinomycin regimen 91 (95%), completed their treatment successfully without requiring additional therapy. For the 142 MTX/FA patients receiving second-line treatment with EMA–CO, only 2 required a further treatment change in both cases to TE/TP because of excess EMA–CO toxicity.

Alongside the majority of FIGO low-risk patients starting treatment with MTX/FA, three low-risk patients received single-agent dactinomycin as their first-line treatment, with two of them requiring additional EMA–CO second-line treatment. As a result of either heavy bleeding, patient choice or concerns regarding the role of MTX/FA in patients with very high hCG levels, 22 low-risk patients were electively started on first-line therapy with EMA–CO, and all were successfully treated with this as their first-line therapy as reported in a previous publication (McGrath et al, 2010).

High-risk group

High-risk disease with a FIGO score in excess of 6 is relatively rare in the post-mole GTT population, with only 39 (6%) patients in this group. Of these, three chose to have first-line treatment with MTX/FA, which was unsuccessful in all. These patients were then successfully cured with EMA–CO. From the 36 high-risk patients starting with first-line EMA–CO treatment, 33 were cured with this regimen, with the other 3 successfully treated with a change to either cisplatin-based chemotherapy or hysterectomy.

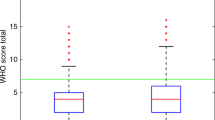

Response by FIGO prognostic score and disease sites

The treatment outcomes of all 618 patients were analysed according to their FIGO prognostic scores as shown in Table 4. This demonstrates the reducing efficacy of MTX/FA with the increasing prognostic score. For patients with a FIGO score of 0 and 1, the primary success rate is 75%, but falls to less than 50% for patients with FIGO scores of 3–5. For patients with a FIGO score of 6 treated with MTX/FA, the primary success rate is 31%; however, it is apparent that only half of this group started on MTX/FA with the others starting directly with more intensive first-line therapies so potentially, positively biasing this result.

The treatment results were also analysed according to the documented sites of disease as shown in Table 5. This demonstrates that from the total of 618 patients, 83 (13.5%) had no visible tumour mass on their routine imaging and that the large majority, 76%, had disease limited to the uterus. The spread of disease beyond the pelvis was rare, occurring in just 10% of the patients, with the lungs being the only documented site of disease. The declining success rate with first-line MTX/FA with more advanced stage matches closely with the results of the FIGO score, ranging from 74% for those with no visible tumour to 55% for patients with disease limited to the uterus, and falling to 36% for patients with lung metastases visible on their CXR.

Relapses

As shown in Table 6, there were 18 relapses from the 618 patients giving an overall risk of relapse of approximately 3%. All the patients who relapsed had originally been within the FIGO 0–5 score groups. Treatment had been with MTX/FA alone in nine of them and combined with either dactinomycin or EMA–CO for the others.

On relapse, 13 of the patients received EMA-CO treatment to achieve cure, 4 had chemotherapy with the TE/TP regimen and 2 patients underwent a hysterectomy. All of the relapse patients were successfully salvaged and cured.

Discussion

Gestational trophoblast tumours occurring after a molar pregnancy have been routinely curable with chemotherapy for over 50 years (Hertz et al, 1956). However, these tumours are rare in any individual hospital and their effective treatment considerably predates the modern era of randomised clinical trials. As a result, the current standard treatment protocols are based on empirical observations but are supported by a number of larger treatment series, such as this and others, published both by our group and other GTT units (McNeish et al, 2002; El-Helw et al, 2009; Fulop et al, 2010).

Overall post-mole GTT is an illness in which the expectation from treatment is one of cure; the data in this study demonstrates in Table 3 that all 618 patients were successfully treated. The majority of patients only required treatment with low-toxicity single-agent chemotherapy, whereas 34% of patients required combination chemotherapy, and only 2 patients required a hysterectomy. This data is similar to our previous cohort and for other treatment series, both from the GTT service in Sheffield (El-Helw et al, 2009), and other centres in Europe (Chalouhi et al, 2009; Fulop et al, 2010), Asia (Kang et al, 2010) and North America (Hoekstra et al, 2008; Growdon et al, 2010).

The standard assessment of GTT patients includes the FIGO prognostic score, which is based on a number of key clinical parameters and allows an estimate of the likely first-line cure rate with the low-intensity single-agent drug treatment. During the study period, 94% of the post-molar pregnancy GTT patients fell into the FIGO low-risk grouping. The value of the prognostic scoring is reflected in a falling success rate of first-line therapy with a rising FIGO score. For FIGO scores 0 and 1, the rate is 75% but falls to just under 50% for groups 3–5, whereas for patients in the prognostic score 6 group the success rate for MTX/FA was 31%. However, almost 50% of this prognostic score group were electively treated with more intensive chemotherapy from the outset, as they were judged unlikely to respond satisfactorily to MTX/FA. As a result, it is likely that true overall success rate for MTX/FA in FIGO score 6 patients could be considerably lower.

The management of patients with prognostic scores of 4–6 has been an area of debate, with some groups treating these patients as an ‘intermediate-risk group’ and receiving first-line treatment with dactinomycin (McNeish et al, 2002). Currently, the debate regarding the more formal introduction of the intermediate grouping is ongoing (Aghajanian, 2011) and a multicentre trial examining the comparative benefits of MTX and actinomycin is opening shortly. The data in this paper may help reflect what the results of the current MTX/FA-based treatment delivers and support the discussion on the subject.

Although the FIGO scoring system is now the most widely used approach to determine prognosis and first-line treatment intensity, historically a number of patients are treated following assessment on conventional staging (Homesley, 1994). The results in Table 5 demonstrate the disease locations for the 618 patients treated and their treatment outcome with first-line MTX/FA treatment. Of the group, only 10% had spread outside of the pelvis, with lung metastases visible on their CXRs. Of note, during routine staging and more extensive CT staging in selected patients, no cases of spread to any other sites were documented in any of these post-mole GTT patients.

The first-line treatment outcome shows that the anatomical staging results parallel the FIGO system, with more advanced disease being less likely to be cured with single-agent MTX/FA. The MTX/FA success rates were 74% for those with serological disease only, 55% for those with disease limited to the uterus and only 36% for those with lung metastases.

For patients who were started on MTX/FA, but developed evidence of MTX resistance, we have historically used an hCG cut-off value of 100 IU l−1 to determine with single-agent dactinomycin or a combination EMA–CO is used as the second-line treatment. In this recent study, we have used a higher cut-off value of 300 IU l−1, which has produced an overall second-line dactinomycin success rate of 94% that compares favourably with the 87% reported when the cut-off value was 100 IU l−1. With this update, we are confident that dactinomycin can be safely used in these patients with a high chance of cure and much lower toxicity than would occur with the EMA–CO treatment.

Following successful therapy relapse of post-mole GTT is rare, with the data in Table 6 showing an overall relapse rate of 3.3%. The relapses were fairly evenly distributed among patients treated with MTX/FA and those receiving more complex therapies. Fortunately, all the relapse patients were cured with additional salvage chemotherapy or surgery. The low rate of relapse and high subsequent cure rate supports a policy of informing treated patients that they are almost certainly cured (97%), but that they should take part in a structured hCG follow-up programme because of the small (3%) chance of relapse.

Overall, the data in this series confirms that the previously reported uniform cure rates for patients with post-molar pregnancy GTT supports the grading of treatment intensity using the FIGO scoring system, and may be of value to others treating GTT in designing clinical trials, developing centralised treatment centres or updating therapeutic guidelines.

Change history

09 November 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aghajanian C (2011) Treatment of low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. J Clin Oncol 29: 786–788

Alazzam M, Tidy J, Hancock BW, Osborne R (2009) First line chemotherapy in low risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: (CD007102)

Bower M, Newlands ES, Holden L, Short D, Brock C, Rustin GJ, Begent RH, Bagshawe KD (1997) EMA/CO for high-risk gestational trophoblastic tumors: results from a cohort of 272 patients. J Clin Oncol 15: 2636–2643

Bower M, Rustin GJ, Newlands ES, Holden L, Short D, Foskett M, Bagshawe KD (1998) Chemotherapy for gestational trophoblastic tumours hastens menopause by 3 years. Eur J Cancer 34: 1204–1207

Chalouhi GE, Golfier F, Soignon P, Massardier J, Guastalla JP, Trillet-Lenoir V, Schott AM, Raudrant D (2009) Methotrexate for 2000 FIGO low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia patients: efficacy and toxicity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 643.e1–643.e6

El-Helw LM, Coleman RE, Everard JE, Tidy JA, Horsman JM, Elkhenini HF, Hancock BW (2009) Impact of the revised FIGO/WHO system on the management of patients with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 113: 306–311

Fülöp V, Szigetvári I, Szepesi J, Végh G, Bátorfi J, Nagymányoki Z, Török M, Berkowitz RS (2010) 30 years’ experience in the treatment of low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia in Hungary. J Reprod Med 55: 253–257

Growdon WB, Wolfberg AJ, Goldstein DP, Feltmate CM, Chinchilla ME, Lieberman ES, Berkowitz RS (2010) Low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and methotrexate resistance: predictors of response to treatment with actinomycin D and need for combination chemotherapy. J Reprod Med 55: 279–284

Hertz R, Li MC, Spencer DB (1956) Effect of methotrexate therapy upon choriocarcinoma and chorioadenoma. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 93: 361–366

Hoekstra AV, Lurain JR, Rademaker AW, Schink JC (2008) Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: treatment outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 112: 251–258

Homesley HD (1994) Development of single-agent chemotherapy regimens for gestational trophoblastic disease. J Reprod Med 39: 185–192

Kang WD, Choi HS, Kim SM (2010) Weekly methotrexate (50 mg/m(2)) without dose escalation as a primary regimen for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 117: 477–480

Lertkhachonsuk AA, Israngura N, Wilailak S, Tangtrakul S (2009) Actinomycin d versus methotrexate-folinic acid as the treatment of stage I, low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19: 985–988

McGrath S, Short D, Harvey R, Schmid P, Savage PM, Seckl MJ (2010) The management and outcome of women with post-hydatidiform mole ‘low-risk’ gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, but hCG levels in excess of 100 000 IU l(-1). Br J Cancer 102: 810–814

McNeish IA, Strickland S, Holden L, Rustin GJ, Foskett M, Seckl MJ, Newlands ES (2002) Low-risk persistent gestational trophoblastic disease: outcome after initial treatment with low-dose methotrexate and folinic acid from 1992 to 2000. J Clin Oncol 20: 1838–1844

Ngan HY, Bender H, Benedet JL, Jones H, Montruccoli GC, Pecorelli S (2003) Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 83 (S1): 175–177

Rustin GJ, Newlands ES, Lutz JM, Holden L, Bagshawe KD, Hiscox JG, Foskett M, Fuller S, Short D (1996) Combination but not single-agent methotrexate chemotherapy for gestational trophoblastic tumors increases the incidence of second tumors. J Clin Oncol 14: 2769–2773

Savage P, Seckl M, Short D (2008) Practical issues in the management of low-risk gestational trophoblast tumors. J Reprod Med 53: 774–780

Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS (2010) Gestational trophoblastic disease. Lancet 376: 717–729

Wang J, Short D, Sebire NJ, Lindsay I, Newlands ES, Schmid P, Savage PM, Seckl MJ (2008) Salvage chemotherapy of relapsed or high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) with paclitaxel/cisplatin alternating with paclitaxel/etoposide (TP/TE). Ann Oncol 19: 1578–1583

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sita-Lumsden, A., Short, D., Lindsay, I. et al. Treatment outcomes for 618 women with gestational trophoblastic tumours following a molar pregnancy at the Charing Cross Hospital, 2000–2009. Br J Cancer 107, 1810–1814 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.462

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.462

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Gestational trophoblastic disease: an update

Abdominal Radiology (2023)

-

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia with extrauterine metastasis but lacked uterine primary lesions: a single center experience and literature review

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

Efficacies of FAEV and EMA/CO regimens as primary treatment for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

British Journal of Cancer (2022)

-

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia: Rationale, Effectiveness, and Future Fertility

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2022)

-

Pulse actinomycin D as first-line treatment of low-risk post-molar non-choriocarcinoma gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

BMC Cancer (2018)