Abstract

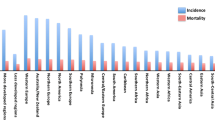

This study examined disparities in cervical cancer mortality rates among US women in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas from 1950 through 2007. Inequalities in incidence, stage of disease at diagnosis, and patient survival were analyzed during 2000–2008. Age-adjusted mortality, incidence, and 5-year relative survival rates were calculated for women in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, and differences in relative risks were tested for statistical significance. Log-linear regression was used to analyze annual rates of change in mortality over time. During the last five decades, women in non-metropolitan areas had significantly higher cervical cancer mortality than those in metropolitan areas. Disparities persisted against a backdrop of consistently declining mortality rates. Throughout 1969–2007, both white and black women in non-metropolitan areas maintained significantly higher cervical cancer mortality rates than their metropolitan counterparts. Among black women, cervical cancer mortality declined at a faster pace in metropolitan than in non-metropolitan areas. In both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, black women had twice the mortality rate of white women. During 2000–2008, white, black, and American Indian women in non-metropolitan areas had significantly higher cervical cancer incidence rates than their metropolitan counterparts. Survival rates were significantly lower in non-metropolitan areas, particularly among rural black women. The 5-year survival rate for black women diagnosed with cervical cancer was 50.8% in non-metropolitan areas, compared with 60.2% for black women and 71.0% for white women in metropolitan areas. Disparities in survival existed after controlling for disease stage. Rural–urban disparities in cervical cancer have persisted despite steep declines in incidence and mortality rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, & Parkin DM. (2010). GLOBOCAN 2008, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC cancer base no. 10 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 22 June 2011.

Howlader N, Noone AM, & Krapcho M, et al (Eds). (2011). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2008. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/.

Kochanek, K. D., Xu, J. Q., Murphy, S. L., et al. (2011). Deaths: Preliminary data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 59(4), 1–68.

Xu, J. Q., Kochanek, K. D., Murphy, S. L., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2010). Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 58(19), 1–136.

Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, & Edwards BK. (2003). Area socioeconomic variations in US cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series, No. 4. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. NIH Publ No. 03-5417.

Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, & Edwards BK. (2004). Persistent area socioeconomic disparities in US incidence of cervical cancer, mortality, stage, and survival, 1975–2000. Cancer 101(5), 1051–1057.

Singh, G. K., & Siahpush, M. (2001). All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(3), 392–399.

Benard, V. B., Coughlin, S. S., Thompson, T., & Richardson, L. C. (2007). Cervical cancer incidence in the United States by area of residence, 1998–2001. Obste Gynecol, 110(3), 681–686.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2006). Healthy people 2010: Midcourse review. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). Healthy people 2020. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx. Accessed 22 June 2011.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2011). National vital statistics system, mortality multiple cause-of-death public use data file documentation. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_public_use_data.htm. Accessed 17 May 2011.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2011). Health, United States, 2010 with special feature on death and dying. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Butler MA, & Beale CL. (1994). Rural-urban continuum codes for metro and nonmetro counties, 1993. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. Staff report 9425.

Bureau of Health Professions. (2010). Area resource file, 2009–2010, technical documentation. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration.

Singh, G. K., & Siahpush, M. (2002). Increasing rural-urban gradients in US suicide mortality, 1970–1997. American Journal of Public Health, 92(7), 1161–1167.

US Census Bureau. (2003). 2000 Census of population and housing, summary file 3, technical documentation. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce.

Singh, G. K. (2003). Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1137–1143.

Singh, G. K., & Kogan, M. D. (2007). Widening socioeconomic disparities in US childhood mortality, 1969–2000. American Journal of Public Health, 97(9), 1658–1665.

American Cancer Society. (2010). Cancer facts and figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

Coughlin, S. S., Thompson, T. D., Hall, H. I., et al. (2002). Breast and cervical carcinoma screening practices among women in rural and nonrural areas of the United States, 1998–1999. Cancer, 94(11), 2801–2812.

de Sanjose, S., Bosch, F. X., Munoz, N., & Shah, K. (1997). Social differences in sexual behaviour and cervical cancer. IARC Sci Publ, 138, 309–317.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2009). The national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), 2005–2008 public use data files. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm. Accessed 22 June 2011.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Human Subjects Review

No IRB approval was required for this study, which is based on the secondary analysis of public-use federal databases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily those of the Health Resources and Services Administration or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, G.K. Rural–Urban Trends and Patterns in Cervical Cancer Mortality, Incidence, Stage, and Survival in the United States, 1950–2008. J Community Health 37, 217–223 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9439-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9439-6